Behavioral science has faced some significant blows in 2023. One of the major reasons for the ongoing replication crisis in behavioral science is the considerable time and funding required to replicate any given experiment.

A promising solution to this lies in the use of generative AI through the generation of synthetic survey data. There’s now a considerable body of research showing large language models to be an adequate substitute for human participants. This new method could potentially accelerates the replication process, cheaply.

I test this idea with the new edsl package by replicating one of the experiments in the retracted Gino, Kouchaki, and Galinsky (2015) study.

The Experiment

Experiment #4 from the (now retracted) study “The Moral Virtue of Authenticity: How Inauthenticity Produces Feelings of Immorality and Impurity” goes as follows:

Harvard undergrads were asked for their opinions on a campus issue: whether course difficulty ratings should be included in a course guide. Students were assigned to write an essay either supporting or opposing the inclusion of these ratings, with some students having a choice in the matter and others not. After flexing their persuasive writing muscles, students rated how desirable various products (like Dove soap, Crest toothpaste, and PostIt notes) were to them. The point was to see whether feeling out of touch with their ‘real selves’ made them feel like taking a shower (hence the Dove soap). The (now retracted) study finds that the study participants desired cleansing products more when arguing against their own initial stance.

Data Colada does a Data Piñata

Data Colada‘s post, titled ‘Data Falsificada (Part 2): ‘My Class Year Is Harvard,’ describes in detail how the data tampering for this study was uncovered. Specifically, Data Colada researchers have used the publicly available survey response data and found some peculiar irregularities:

[…]. In the “yearSchool” column, you can see that students approached this “Year in School” question in a number of different ways. For example, a junior might have written “junior”, or “2016” or “class of 2016” or “3” (to signify that they are in their third year). All of these responses are reasonable.

A less reasonable response is “Harvard”, an incorrect answer to the question. It is difficult to imagine many students independently making this highly idiosyncratic mistake. Nevertheless, the data file indicates that 20 students did so.

Data Colada researchers end up showing that the idiosyncratic responses labeled “Harvard” disproportionately support the study’s hypothesis. Yikes.

Simulated Experiment #4

I use the ability of language models to simulate human behavior and replicate Experiment #4 as closely as possible. How?

This calls for a separate post, but the gist of it is – I use an awesome new Python package called edsl (“Emeritus Domain-Specific Language”) developed by John Horton and team. This package allows to create and simulate surveys using a number of large language models, and varying conditions, scenarios, and characteristics of synthetic respondents. It is really, really cool.

To replicate the experiment, I first generate a population of 750 students (N=491 in the original study), endowing each with randomly assigned traits like major, year, and interests. These endowed traits are highly customizable.

MAJORS = ['Economics', 'Computer Science', 'Biology', 'History', 'Psychology']

YEARS = ['Freshman', 'Sophomore', 'Junior', 'Senior']

INTERESTS = ['Technology', 'Sports', 'Arts', 'Science', 'Literature']I then create a survey that mimics the structure of the original study closely. I first gather agents’ demographics and initial opinions on a campus issue (inclusion of difficulty ratings in a course guide). Next, I ask each agent to write an essay either supporting or opposing their original view on the campus issue, and finally capture their product preferences and feelings of inauthenticity.

Obviously, the results I get differ from the original study – duh. First, there are no mislabeled observations (as neither the LLM nor I are up for tenure1). The language model (GPT4) also refused to provide personally identifiable information (PII), such as student id and email.

Otherwise, it did great – there was even no need to explain what Q Guide is – it already knew (I didn’t). The model temperature was set at 0.5, so the written responses were not as diverse and interesting as one would get from actual students, but quite good nonetheless.

For example, on feeling inauthentic while writing an essay:

“While I did have to incorporate some perspectives that aren’t entirely my own, I found a way to align most of the essay with my authentic views, so I felt only moderately inauthentic.”

“I felt mostly authentic while writing the essay as it reflected my own thoughts and understanding.”

On Q-Guide difficulty rating inclusion:

“Yes, I believe including difficulty ratings in the Q guide would be beneficial as it helps students make informed decisions about course selection relative to their own strengths, workloads, and academic plans.”

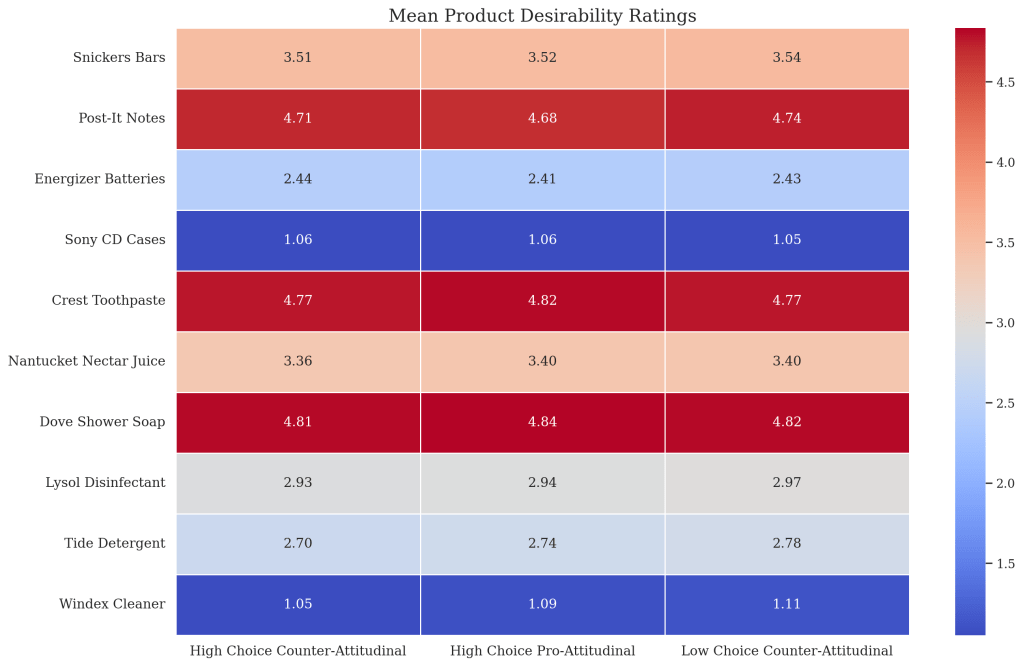

So, did the synthetic respondents end up feeling dirty after arguing against their initial point of view? The heatmap below provides a visual representation of the mean product desirability ratings across three different essay types: high choice counter-attitudinal, high choice pro-attitudinal, and low choice counter-attitudinal. Each column represents one of these essay types, while each row corresponds to a specific product, ranging from Snickers bars to Windex cleaner:

I ran a set of t-tests between the sets of simulated student groups to mimic the analysis of the original study. The series of t-tests across products consistently revealed no statistically significant differences in product desirability ratings between the (strongly enforced) counter-attitudinal and pro-attitudinal groups, suggesting that the type of essay does not significantly influence participants’ product preferences. For the (weakly enforced) counter-attitudinal and pro-attitudinal groups, the results were the same.

What to make of this? Since this is a retracted study (that was not replicated elsewhere, afaik), I do not know. I don’t know whether this premise holds with respect to human behavior in general. The idea itself kind of makes sense to me – I do sometimes feel like eating Tide pods after networking.2 Perhaps having people argue a much more contentious point that goes completely against their beliefs would result in them craving some Lysol? Perhaps. Any takers?

Leave a comment