While model estimation has made significant progress over the past two decades, model generation remains a relatively unexplored area. This new working paper by Ben Manning, Kehang Zhu, and John Horton ventures into this unexplored territory by proposing a new model generation technique.

How? Well, we know that:

- Machine learning can be used for automated hypothesis generation (e.g., 1; 2)

- Large Language Models (LLMs) can simulate human subjects for testing hypotheses (e.g., 1; 2; 3; 4, and many others)

The paper uses LLMs for both generating (1) and testing (2) hypotheses. Another cool element is the use of structural causal models (Pearl, 2009b) to provide a framework to state hypotheses.

What does this mean and how does this work? Here is an outline of the process:

| Step 1: a researcher comes up with ANY scenario of interest, e.g., a negotiation, a bail decision, a job interview, an auction, and so on. |

| Step 2: the system generates outcomes of interest and their potential causes, |

| Step 3: the system creates agents that vary on the exogenous dimensions of said causes, |

| Step 4: the system designs an experiment, |

| Step 5: the system executes the experiment with LLM-powered agents simulating humans, |

| Step 6: the system surveys the agents to measure the outcomes, |

| Step 7: the system analyzes the results of the experiment to assess the hypotheses, and |

| Step 8: the system plans a follow-on experiment based on the derived results. |

SCMs comes into play in Step 2. We want to know how a cause (like education) affects an outcome/effect (like income). SCMs can precisely tell us the minimal set of exogenous variables we need to manipulate (exogenously) to study this cause-and-effect relationship. The LLM is thus prompted to create each explanatory variable describing something about a person or scenario that must vary for the effect to be identified. This information is then used in Step 3 to generate agents that vary on those dimensions.

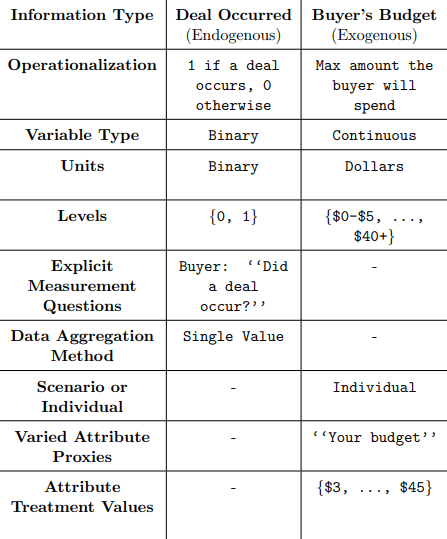

Let’s take an example from the paper to demonstrate this process. The social scenario of interest (Step 1) is “two people bargaining over a mug”. Taking this phrase as the only input (!), the LLM produces a potential outcome: “whether a deal occurs for the mug” and operationalizes the outcome as a binary variable with a ‘‘1’’ when a deal occurs and a ‘‘0’’ when it does not. In general, for each endogenous variable, the system generates an operationalization, a type, the units, the possible levels, the explicit questions that need to be asked to measure the variable’s realized value, and how the answers to those questions will be aggregated to get the final data for analysis. It then generates potential exogenous causes, their operationalizations, and other relevant attributed.1

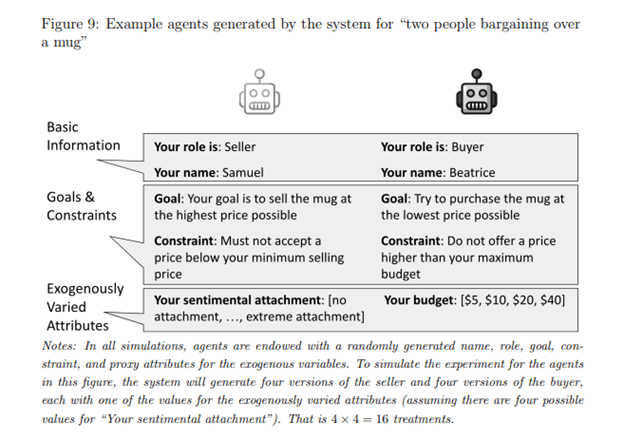

Next, agents are constructed via prompting, e.g.: “You are a buyer in a negotiation scenario with a seller. You are negotiating over a mug. You have a budget of $20.” The SCM attributes are included, but there are others that can be incorporated. One can generate whatever number of different agents, and whatever number of different attributes, depending on one’s goals.

Each agent is randomly assigned attributes, including names (having identifiers helps agents address each other in simulations), roles (e.g., buyer), goals (e.g., buy the mug at the highest price possible), constraints (e.g., don’t spend more money than you have), and proxy attributes for exogenous variables (e.g., budget). The system simulates different treatments by varying the exogenously varied attributes.

Once the agents are created, the system executes the experiment (Step 5). In this example, we have a multi-agent simulation, and so, there must be a speaking order. What should the speaking order be? There is no obvious answer to that, as it depends on the interaction at hand. The authors consider a number of protocolos, depending on the scenario at hand:

Each simulation runs in parallel. Agents are provided with a scenario, their attributes, the other agents’ roles, any scenario-level attributes, and access to the transcript of the conversation. Then, they interact according to the chosen interaction protocol.

But when to end this simulation? The authors implemented a two-tier mechanism to determine when to stop each simulation. There is a coordinator. After each agent speaks, the coordinator receives the transcript and decides if the conversation should continue or not. Additionally, simulations are limited to 20 statements across all agents in the scenario, not including the coordinator.

Following a simulation, the system administers a survey to assess the outcome variable of interest for each participant. It records their responses to questions predetermined by the structural causal model. The language model assists in assigning correct numerical values to these responses based on the variable type—integers or floats for continuous/count variables, whole-number sequences for ordinal/binary, and dummy vars for categorical. If multiple questions inform a single variable, they are aggregated accordingly. Finally, the system compiles a data frame with numerical values for each SCM variable.

Finally, with a complete dataset and the proposed SCM, the system can estimate the linear SCM without further queries to an LLM. The system uses the R package lavaan to estimate all paths in the model.

To sum it up, the paper shows that it is possible to create a system—without human input at any step (as even Step 1 can be LLM-generated, if needed!)—to simulate the entire social scientific process. Can’t wait to test this approach myself!

- For example, in the proposed scenario, the exogenous variable is “the buyer’s budget”, which is operationalized as the buyer’s willingness to pay in dollars (e.g., {$5, $10, $20, $40}). ↩︎

Leave a comment