What good is synthetic data for? Plenty, says a new working paper by J.P. Morgan AI Research team (yes, they have a dedicated AI Research team). The paper has a lot of good stuff in it. They discuss various techniques for generating synthetic data, and also go into challenges and applications associated with these methods.

The need for synthetic data in finance is obvious if you start thinking about privacy concerns, but there are also other aspects to it. J.P. Morgan folks categorize this need into: data liberation (i.e., data sharing), data augmentation (not enough data on unprecedented events, like certain types of market crashes or operational risk events — may we only ever have synthetic data on these), and generating realistic outcomes of hypothetical scenarios and testing internal systems against those.

So, synthetic data is good for many things, but what is good synthetic data? Sure, there are some existing statistical methods to answer that, e.g., estimating statistical distances between the real and the synthetic. Still, evaluating synthetic data in specific domains (finance and many others) is very much an evolving area.1

Broadly, there are three key metrics by which one can evaluate synthetic data: fidelity, utility, and privacy.

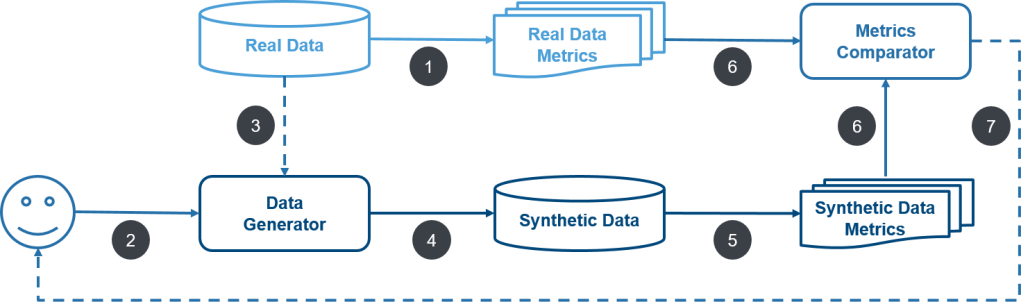

Fidelity: Fidelity tells us whether a certain sample population is relevant to the problem that we’re solving. To assess the relevance of the synthetic data, we must evaluate it in terms of fidelity as compared to the original (e.g., the cardinality and ratio of categories were respected, the correlations between the different variables were kept, and so on). This means that key metrics such as means, variances, correlations, and distributions of the synthetic data should closely match those of the real data. Another important point is that beyond individual metrics, maintaining the relationships and interactions between different variables or features in the data is crucial. For instance, if age and health outcomes are correlated in the real data, this relationship should be preserved in the synthetic data. Consider this shamelessly stolen diagram from the J.P. Morgan website. “Metrics Comparator” would conduct fidelity testing of some kind:

Utility: in this context, utility refers to the effectiveness of a synthesized dataset in addressing typical data science challenges across various machine learning algorithms. Currently, there are no established benchmarks for synthetic financial data. Considering the significant implications—both positive and negative—of synthetic data in finance, it might be prudent for government agencies to step in and establish regulatory standards or benchmarking criteria.

Privacy: privacy considerations in the context of synthetic data are complex. One basic method for assessing privacy is the use of simple checks, such as the ‘exact match score’. Ideally, this score should be zero, indicating that none of the real, original information exists unchanged in the synthetic dataset. This measure acts as an initial filtering step prior to the application of more comprehensive privacy assessments. But there are many other aspects to consider.

Last week I had a chance to attend a lecture by Cynthia Dwork on risk prediction, organized by the Stanford Data Science. The video is now up on youtube. The lecture was somewhat technical, and in between googling math terms and staring at the back of a Nobel Laureate’s head (talk about privacy..), i thought about how this lecture applies to synthetic data in general.

Cynthia discussed the concept of outcome indistinguishability (OI). OI posits the distribution of outcomes in synthetic data to be un–distinguish–able (you’re welcome) from real data. Meaning, for any given analysis, the results obtained from the synthetic dataset should be statistically similar to those obtained from the real dataset. At least theoretically, OI preserves individual privacy while maintaining data’s analytical value. In practice, this means that organizations/researchers can use synthetic data that meets the IO criteria for a wide range of purposes – from predictive modeling to AI training – without compromising on data quality or privacy.

This month has been full of interesting lectures. Another one attended this week was by Vinod Vaikuntanathan, CS professor at MIT. Vinod is a fantastic speaker, and talked about his work involving homomorphic encryption. Simply put, homomorphic encryption enables users to perform analysis and mathematical calculations on encrypted data without compromising its confidentiality. So, sensitive data to be processed without giving access to the raw data. Perhaps encryption is the way to go when it comes to the privacy-utility trade-off (although I imagine this wont be feasible for a lot of real-words applications).

The J.P. Morgan AI Research team classifies the privacy aspects of synthetic data into six distinct levels. Level 1 involves basic measures like the removal of Personally Identifiable Information (PII), while Level 6 represents fully simulated data without any calibration to real-world data. Generative modeling is Level 3. So, somewhat useful and somewhat secure. Which isn’t too shabby.

All of this is incredibly interesting and complex, and there’s still much to be done in this field. But, let’s indulge and dream a little. If you could generate “good” synthetic data, what type of data would you generate?

Leave a comment